Let’s face it, when it comes to hacks we have become, well, quite complacent. We figure it is out of our control anyway and it’s not like we are going to go off grid. Right? Besides its just data, not like they can physically hurt us.

I thought so too until I watched a 2014 video of Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek forcing a Jeep Cherokee to go off the highway into a ditch at full speed. What’s the big deal? THEY WEREN’T IN THE CAR! They were driving behind the Jeep and were able to control it remotely. Scary.

I thought so too until I watched a 2014 video of Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek forcing a Jeep Cherokee to go off the highway into a ditch at full speed. What’s the big deal? THEY WEREN’T IN THE CAR! They were driving behind the Jeep and were able to control it remotely. Scary.

How did they do it? First, they hacked into the vehicle through an unsecure Wi-Fi connection – easy, unfortunately.

But how did they control the car? By hacking the vehicle control network – the CAN Bus.

As cars became more advanced and offered more features the need for a common communication protocol emerged. In 1983, a team at Bosch started developing the Controller Area Network (CAN) Bus to solve this complex problem. New features including airbags, power steering, acceleration, braking, cruise control, audio components, power windows & doors now had a standard way to communicate with each other. These components connect directly to the CAN Bus through Electronic Control Units (ECUs) which primarily consist of microprocessors and sensors. In simplest terms, the CAN bus is a network where any system in the car can send and receive commands, kind of like an electronic command center.

The original CAN Bus was designed at a time when the thought of hacking vehicle software or any software was a far-off thought. It was so incredibly difficult to even write custom embedded code that the idea of someone hacking it was just crazy. Well, here we are at crazy.

The implementation of the CAN bus also allowed car manufacturers to move forward with the On-Board Diagnostics (OBD) protocol standard currently OBD-II. OBD-II offers a set of problem codes that can be easily interpreted by mechanics when trying to diagnose a problem. You can find the typeical OBD port under the steering column.

All you need to buy is a CAN bus module – here’s one from Sparkfun.com (https://www.sparkfun.com/products/13262).

All you need to buy is a CAN bus module – here’s one from Sparkfun.com (https://www.sparkfun.com/products/13262).

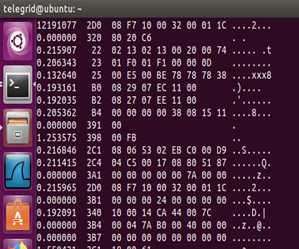

Hook it up to your car’s OBD connector and a laptop and you can see all the information being transmitted on your cars CAN bus. Cool right? But wait – Did it ask you to login?

Nope … and that’s where our problem begins.

The CAN Bus has no security measures, period. Messages are transmitted on the bus with only unique identifiers. The lower the numerical value of the ID, the higher the message priority. The problem is that there is no origination or destination indication transmitted with the message. In a world of TCP/IP the idea that a message can be transmitted without knowing the sender is nuts! This allows ANYONE to transmit messages on the bus with any ID at any time.

Lack of security leaves the CAN Bus susceptible to many different attack scenarios. The easiest attack is a brute force attack where a hacker simply has to transmit high priority messages on the bus at such a high rate that the other messages can’t get through. This will eventually immobilize the car and the driver.

Lack of security leaves the CAN Bus susceptible to many different attack scenarios. The easiest attack is a brute force attack where a hacker simply has to transmit high priority messages on the bus at such a high rate that the other messages can’t get through. This will eventually immobilize the car and the driver.

The real danger, however, is when a sophisticated hacker deciphers valid CAN Bus messages and is able to retransmit them at will which allows a hacker to gain control of the vehicle. (This is also how self-driving cars work – but we will talk about that another time).

So what are we to do? Many ideas have come up about how to implement security. One method calls for adding authentication or encryption to the bus. The issue with these types of methods is that they can introduce latency on the bus which will affect vehicle performance. These methods also call for a network connection to a remote Certificate Authority (CA) and a central powerful processor which do not exist today. These solutions probably will not happen without a complete vehicle network redesign which is a big deal.

Other methods include using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to identify “normal” CAN Bus behavior and then perform anomaly detection. Again, this is a good method but requires a great deal of training to produce a behavioral model. That means countless hours driving different “control” vehicles with different drivers in order to produce unique patterns.

My team at TELEGRID has a different approach that can identify a CAN Bus attacker without affecting the vehicle performance or long training periods. We are currently working on this solution for US military vehicles and can’t discuss it here so give us a call (973.994.4440) for more information.

Apparently one sure security method available today involves ensuring that the external Wi-Fi connections to the vehicle are secure. After the initial Jeep hack, Chrysler secured the Wi-Fi connection that made the hack possible and issued a recall for all at-risk vehicles. Problem solved? Well, no, because a few years later Charlie and Chris were again able to hack into a Jeep vehicle even after the recall through a different open connection. Sigh.

In the meantime, all we can do is hope that car manufacturers will put as much emphasis on vehicle security as they do on heated and cooled seats.

Want to learn more? Check out these links:

http://illmatics.com/carhacking.html

https://www.wired.com/2016/08/jeep-hackers-return-high-speed-steering-acceleration-hacks/

https://medium.freecodecamp.org/hacking-cars-a-guide-tutorial-on-how-to-hack-a-car-5eafcfbbb7ec

Thank you to the TELEGRID team for spending countless hours in the car listening to my country music and to Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek – not all super heroes wear capes.

Thanks for reading and that’s the buzz from the B-hive.

B